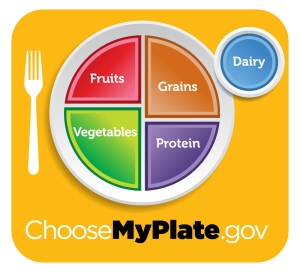

The USDA has released a new graphic concept to replace the old food pyramid as a guide to healthy eating. My Plate is a new approach in the United States to inform the public about creating a balanced meal. With its rich agricultural history, it’s difficult to understand how Americans have distanced themselves so completely from a balanced understanding of food and our relationship to our entire food system. The complexity of our current food dilemma is deep, but not insurmountable. School lunch programs seem to be taking a fair amount of long overdue scrutiny these days, from growing school veggie gardens to revamping lunch rooms into places of nutrition instead of fried potatoes and ketchup. When I saw the My Plate graphic, I immediately thought about school lunch in Japan.

The bento box is an image that seems indelibly linked to a Japanese school child, but in my experience teaching at eight different elementary schools it was school lunch (kyushoku) not O-bento five times a week. Being a non-dairy vegetarian, I had a mixed experience with school lunch. Something that always appears on the school lunch tray is your traditional cardboard container of milk (which students often drank in one giant gulp and quickly flattened to transform into a sort of origami frog). Milk is a leftover dietary staple from post-WWII American reconstruction. When asked why I didn’t drink it and I told people it was because it made sick, many kids and adults said it made them sick too—but they still drank it. For the most part though, school lunch was often more than edible. An acceptable balance of nutrition, locally sourced ingredients, and food education.

Here are some Japanese school lunch principles (based completely on my own observation and experience):

- 5 components: Grain (usually rice), Vegetable (salad), Protein (usually fish or tofu), Soup (miso soup in various forms), Drink (99.9% of the time milk)

- Students serve, say grace together (itadakimasu いただきます and gochisosama-deshita ごちそうさまでした), and clean-up together after the meal.

- Food waste is unacceptable. If they don’t like something, they hold their noses while they eat it.

- A school nutritionist is a full time position in most elementary schools.

- Before the meal, a group of students explain what they are eating that day, and where it came from (often highlighting local or seasonal ingredients).

- After lunch, all the students brush their teeth together to the same, repetitious, frustratingly catchy song (OK, I wanted to find a link so you too could experience the Japanese tooth brushing song… I couldn’t find it, but I did discover a lot of tooth brushing songs that are even worse than the Japanese one!)

I especially like the educational aspect to lunch in Japan, but how to translate that into the typical school lunch in America, where so many bring their own lunch ? One thing we definitely can improve on is less “waste”. At our outdoor overnight camp we weighed the waste (it was call garbology) and it became a competition between groups to see who could have the least left over. Why not tap into America’s competitive nature in a positive way ? it worked ( at least while we were at camp and measuring and learning only to take what you know you can eat).

Pingback: 花見 hanami (blossom viewing) « rice seasons